by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

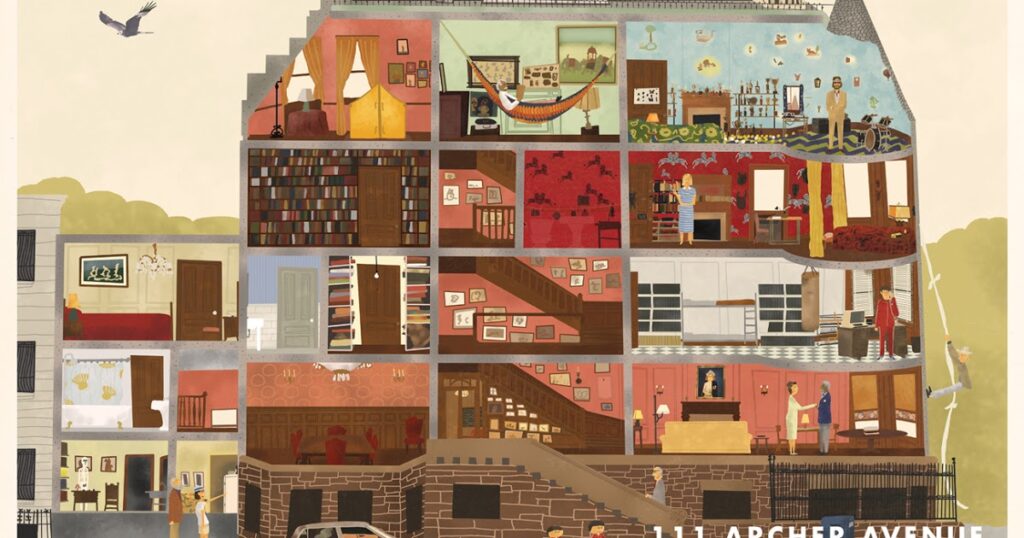

| Please, give me a second grace/ Please, give me a second face. I’ve fallen far down/the first time around/ Now I just sit on the ground in your way. Now, if it’s time to recompense, for what’s done/ Come, come sit down on the fence, in the sun. And the clouds will roll by/and we’ll never deny/ It’s really too hard . . . to fly.—Nick Drake Imperial in manner and impervious to any but his own interests, patriarch Royal Tenenbaum acts out atrociously, conferring “betrayal, failure, and disaster” upon his wife and three precocious prodigies in writer/director Wes Anderson’s melancholy New York story, The Royal Tenenbaums, co-written with Bottle Rocket and Rushmore collaborator, Owen Wilson; original music composed by Mark Mothersbaugh. Royal is the errant center of Anderson and Wilson’s distinctly drawn gallery of idiosyncratic characters. An unfaithful husband and unaware parent, he indulges in deception, favoritism, and occasional thievery with genial charm. Early on, an exasperated Etheline banishes Royal from their Archer Avenue castle: Margot: Are you getting divorced? Royal: It doesn’t look good. Margot: Is it our fault? Royal: [less than reassuring] Obviously we made sacrifices as a result of having children. But no . . . Lord, no. Royal’s subsequent interactions with his offspring are intermittent and marred by Freudian psychodramatics. A sense of entitlement (yet without the proper financial backing) maintains Royal as a guest of the Lindbergh Palace Hotel for twenty-two years until they, too, ask him to leave. And thus Royal re-enters Etheline and his adult children’s lives, certain he can cadge a measure of redemption. What he discovers is a modern day Glass family: numb, suicidal, and hostile towards his infiltration attempts: Royal: You think you can start forgiving me? Chas: Why should I? Royal: [indignant] Because you’re hurting me! A widower with two young sons, Chas has most at emotional stake in the Royal family. Unlike his father, he is protective of Ari and Uzi—but to their detriment. Petrified that death and destruction are imminent, he quells their adventurous nature: Royal: Chas has those boys cooped up like a pair of jackrabbits, Ethel. Etheline: He has his reasons. Royal: Oh, I know that. But you can’t raise boys to be scared of life. You gotta brew some recklessness into them. Etheline: I think that’s terrible advice. Royal: No you don’t. With egregious glee, Royal takes the lads on a tear, exacerbating the conflict. The ensuing argument Royal and Chas have carries on inside the hallway closet where shelves of classic board games line the walls. Fortune 500, Operation, Strategy, Risk, and Last Word exemplify the kind of ingenious storytelling subtlety that makes Anderson and his Go To crew the Head of the (Hollywood) Class. All apologies aside, Royal remains constant in his slippery solipsism, try as he might to change. It is finally Chas who veers off his intractable course of righteousness and forgives his father. Soon thereafter, Royal suffers a fatal heart attack. The epitaph on his headstone, authored by his own hand (and proofread by Etheline at his request), reads: “Died tragically rescuing his family from the wreckage of a destroyed sinking battleship.” The listing vessel none other than himself, Royal O’Reilly Tenenbaum. |