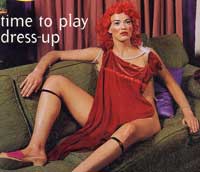

by Katharine E. Monahan Huntley

C. Houston Sams is from Texas (San Antonio) — but she is no relation to famous fellow Texan Sam Houston. The “C” stands for Charlene. As is in Dallas’s Charlene Tilton. Although both blonde, there is no confusing J.R. Ewing’s baby sister’s baby doll persona with the prep school punk rock fashion plate whose cool client list ranged from the commercial to the cult. Celebrities (Quentin Tarantino, Tracy Lords), musicians (Tenacious D, Midget Handjob), and magazines Spin, Nylon, Blender, Premiere, Hollywood Life, Bikini Ray Gun . . .

When did you first become interested in fashion?

Houston: At thirteen I took my first trip to Dallas. It was there I came across a vintage boutique. I thought, “How cool are these clothes.” It was 1980, and I didn’t care for contemporary trends — I liked the 50s styles. Vintage opened up a new world for me. I started making stuff. Sewing and creating. The dilemma was — I didn’t have anywhere to wear my new wardrobe.

Fast forward 8 years. Houston and her retro wardrobe go to Hollywood.

Houston: I started taking classes at UCLA and with that, raking up debt. That got old fast. I had to get a real job. I had nothing to wear for interviews but my 50s and 60s apparel. I answered an ad in the Recycler: “Actress needs assistant.” I put on my “Marilyn Suit” — a baby blue fitted three quarter length sleeve jacket and a pencil skirt. Platinum blonde bobbed hair. As fate would have it, the actress was this redheaded woman, Susan Bernard, the daughter of Bruno Bernard: “Bernard of Hollywood.” He was the glamour photographer for, among others, Sophia Loren, Jayne Mansfield, and, of course, Marilyn Monroe.

WBTL: You were in costume for the job.

Houston: Her son is Joshua Miller, one of kids in Rivers Edge.

Rivers Edge, a seminal independent film, is almost as terrifying as Joshua Miller’s father Jason Miller’s film, The Exorcist, in which he plays Father Damien Karras.

Houston: I would help Susan market the photos. Read the “Breakdown” for Joshua, a daily paraphrased list of auditions for roles agents are preparing to cast. You can identify what character types they are looking for and choose what roles might work for a particular actor. All the major talent agencies get it. . . . Around Halloween I was telling Joshua about my costume: a she-devil on wheels. I explained, ‘You know—like Russ Meyers’ films?’ He exclaimed, “What? Mom was in the Russ Meyers’ Faster Pussycat Kill Kill.”

“A cornerstone of both camp and punk cultures —no mean feat — Faster Pussycat Kill! Kill! (1966) shows the thrillingly lethal consequences when aggravated go-go dancers get bored. Russ Meyer’s black-and-white desert Gothic melodrama — for some viewers the crown jewel in a flashy career . . .” (Morris, Bright Lights Film Journal).

Houston: She came to my party in Hollywood, and all my friends were asking for her autograph. After working with her for a year and a half, I was inspired by the images . . . I needed to go do that — take photos and learn more of the technical aspects of my trade. Including plain old sewing.

After all this I met a girl at a party and she was wearing the coolest thing. She was a costume designer. I asked her about it, and she introduced me to Louise Mingenbach (The Usual Suspects, X-Men, X2, Starsky & Hutch). Up until that point, movies had never occurred to me . . .

The fashion fabulist will eventually return with the entire story, including tales of how working with Melanie Griffiths is not Another Day in Paradise — but how working From Dusk Till Dawn with Roberto Rodriguez is, anecdotes about Judith Frankland, Dogtown and Z-boys, The Gettys, Pleasant Gheman, and just what exactly it is a wardrobe stylist does.