What? The Dickens? Yo!

NoHo. More Shakespeare than Glee.

It’s Something to Sea.

Fig. It. Out.

“And that’s my story.”

With a dramatic flourish and certain finality, dowagers Helen O’Malley and Bow Ross finish the dish.

— Ladies’ Luncheon at Abraham & Strauss, Brooklyn, New York, circa 1957

What? The Dickens? Yo!

NoHo. More Shakespeare than Glee.

It’s Something to Sea.

“Who’s been doing your hair?”—Shampoo

“Who’s been doing your hair?”—Blow

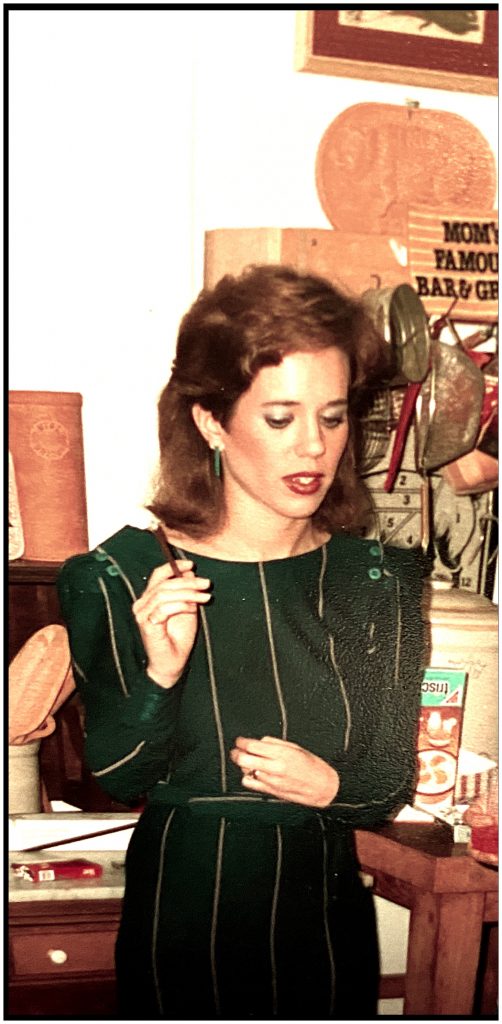

Gazing beneath Los Angeles glitz, the obvious and overt in ‘n’ out of favor flavors, one can encounter a creative arts underground. The scene shifts, trends tire, still the beat goes on. At the core are the anonymous denizens of the in-crowd who give these punk rock artists a name. Fan the fame. Kim Lipot Ochoa cues their look.

Outlasting those who overdosed, and the poseurs who “did it for the fashion,” for more than four decades Kim has maintained her personal impact by creating a unique image for others. In the salon or social swirl, the Kim constellation embodies the two or three degrees of separation that edge the brazen and beautiful of Hollywood’s underworld.

What follows are fragments of cocktail-fueled conversations about what it means to be undeniably cool and almost famous in the land of La Di Da.

Valley Girl

“Fuck you. Fuck off for sure, like totally.”—Valley Girl

What’s the difference between punk rock life in hip Hollywood and a prefab existence in my so-called vacuous Valley?

RANDY

This is the real world. It’s not fresh and clean like a television show . . . We’re ourselves . . . you’re all fucking programmed.

JULIE

So, what does it take to be so free?

RANDY

That’s a good question.

For one Valley girl, the answer equaled X.

Kim Lipot graduated from Kennedy High School class of 1980—smart, shy, and sixteen years old. Nixing the “Oh, I’ll just hang out plans,” Kim’s suburbanite mother arranged for her daughter’s entrance into the material world of 9 to 5.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: A friend of mine has a bit part in Valley Girl. He says that’s what you do growing up in L.A. Leave the long boulevards in the dry hot summers and go to the beach. Get cast as an extra in movies.

Kim: My friends and I went to Zeroes beach, up the coast from Zuma. I had a white Volkswagen campervan and a license a 22 year old had left at my drive-thru bank teller window. She never came back for it. On the weekend, we would buy liquor at Alpha Beta and drive around to house parties.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: So how did you get into punk rock?

Kim: My prom date lent me his X album.

The Starwood

“Days change to night/Change in an instant.”—Los Angeles

Kim: I found out X was playing at The Starwood. My girlfriend and I put black roux rinse in our blond surfer girl hair so we wouldn’t stand out. It turned steel metal gray. We went anyway. The scene was great. The Odyssey, The Seven Seas, Club Lingerie . . . crowded hardcore shows with twenty-five guys to every girl. New Wave Music, The Go-Go’s, B52’s .

Boogie Nights

“All the drugs are at The Starwood.”—Wonderland

Spinning around in Kim’s hair chair. With equal concentration, she expertly mixes colors and listens to the salon buzz as we discuss P.T. Anderson’s Boogie Nights.

Kim: I used to go dancing at the movie’s club, “Hot Traxx.” It was an all ages club on Sherman Way—called The Reseda Country Club.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: The scene between Amber Waves and Rollergirl is cocaine classic. Making plans, yet never leaving the room.

Kim: We’ve all had that conversation.

Decline and Fall of Western Civilization

“Punk rock. That’s stupid. I just think of it as rock and roll ‘cause that’s what it is. . . . It’s for real . . .There’s no rock stars.”—Eugene, Decline and Fall of Western Civilization

Penelope Spheeris documentary explores anarchic behavior in the context of L.A. punk rock. The attraction to rebellion, the insightful music—intoxicating to the tightly wound and aimless ramblers alike. Black Flag lyrics express why the fury needs its sound. With no outlet, the consequences of unreleased tension and boredom may be fatal. “Depression—it’s gonna kill me. It’s gonna kill you too.”

Spheeris casts a grim shadow over this scene—point of fact John Doe tells her: “Reality is dark.” Twenty-five years later, Brendan Mullen and Mark Spitz proclaim in Spin, “SoCal punk has always been about anger.”

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: What about the angst?

Kim: Punk rock has always had its dark side. Everyone felt like an outsider, yet we knew we were involved in something unique. I found my place. Where I fit in.

At nineteen Kim enrolled in beauty school. Classes were from 1:00 pm to 10:00 pm. Quite conducive to the clubbing lifestyle. Glam-o-rama.

Colleen: I was fourteen and in high school. Kim would cut my hair at the beauty school. I became her hair model for salon interviews. Growing up, Kim lived catty corner to me and my two older sisters, Kathleen and Eileen. Kathleen was a “girlfriend” of The Bay City Rollers and John Waite—among others. She claimed “Missing You” was written about her. She and John Waite had the same color auburn hair. That was their connection. Kathleen ran away at sixteen.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Rock and roll fantasyland.

Colleen: Eileen and another friend of Kim’s, Nora Edison, all hung out and I tagged along. Nora dated Louie, a drummer for DC3, and I lived in Venice Beach. Punk rockers and poets. Skateboarders like Tony Alva. That’s where I met Eugene. His claim to fame was the Penelope Spheeris documentary. He took me out to dinner dressed in a 1960s retro suit. He asked me to be his girlfriend. When I said, “No,” he accused me of slumming it. I wasn’t slumming it—I just thought it was too much for a freshman.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Fast times at Kennedy High.

Kim: I went up to Oakland with Louie and the band. DC3 had a gig at The Covered Wagon in San Francisco.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: I saw my brother-in-law’s cousin, Nate Kato of Urge Overkill, at The Covered Wagon. Before they covered Neil Diamond for Pulp Fiction. Before Blackie’s heroin addiction. Whatever became of Louie?

Kim: Overdose.

Sex. Drugs. Punk Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Make the Music Go Bang!

“The strong bond between bands and audiences was helped by the fact that the majority of these groups were not on the ego-tripping “We’re rock stars” excursion. The members were fairly accessible and friendly—they would hang out and drink with the people who came to see them, and this helped break down the barriers created by all the “mega-stars.”—Keith Morris

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: How did you go from fanland to “I’m with the band?”

Kim: A girlfriend I hadn’t seen for awhile came into the beauty school. She invited me to a Judas Priest concert at the Long Beach Arena. Greg Hetson, guitarist for the Circle Jerks, came with us. We started dating almost right away and were together for the next seven years. Keith Clark, the Circle Jerk’s drummer, and I would count the money after every show. Count it, divide it, pay it out. Now Keith’s my accountant, and Greg and I are Facebook friends. He recently reminded me about feeding the baby giraffe at the zoo.

It’s hands off nowadays for L.A. Zoo’s Giraffa camelopardalis subspecies tippelskirchii.

Repo Man

Repo Man featured the Circle Jerks, heightening the fantasy/reality aesthetic of the film. Humor stops the theme of alienation short of annihilation.

Punk

I blame society. Society made me what I am.

Otto

That’s bullshit. You’re a white suburban punk just like me.

Kim: The coolest people in the scene lived in nice suburban houses with their parents. Yeah, there were some that lived on the streets—but they really didn’t want to be there. Who would?

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: A mutual acquaintance was just telling me about her racing down Lankershim w/Corey Haim in the wee morning hours, Bret Easton Ellis scene style.

X Man

“I head for the Roxy, where X is playing. . . . they’re going to be singing “Sex and Dying in High Society” any minute now . . .”—Less Than Zero

Kim: Greg, Keith Morris, John Doe, and I drove down to San Diego for a spoken-word performance. Greg played acoustic guitar—which he never liked to do. We drank beer and were bored for five hours. When it came time to go, Keith was too drunk and Greg too tired to drive. I hate driving. John Doe stepped into the driver’s seat, looked at me, and said, “Baby, that’s what I’m here for.” I sat up front and listened to Joh Doe the entire ride home. Transfixed. From then on, whenever we would see each other at a show, he would always say, “Hello.”

Reality Bites

And then it was Nirvana and the 90s. Punk became pop flavor. Kim and Greg parted ways. New decade. New boyfriends. Always new hairstyles.

Kurt and Courtney

“Fame is a process of isolation.”—Kurt and Courtney

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: I loved the Kurt and Courtney documentary. Ridiculous and enormously entertaining. Nick Broomfield with his British accent—never veering from his serious “journalist” façade makes it almost believable.

Kim: Anyone who’s been in L.A. for a length of time knows Courtney Love. Before Kurt, she was a stripper married to a friend of mine. A writer for the L.A. Weekly. A transvestite who . . .

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Lest we forget what happened to El Duce, keep the rest of your story L.A. confidential. Just in case Courtney is a killer.

Al’s Bar + Spaceland

“There are people possessive of the early punk scene. They try to hold on to it, but years go by all by themselves. There’s still a scene. It’s a bit modified, but any night of the week you can hear the music.”—Craig Ochoa

In 1996 Kim married musician Craig Ochoa. His band, Gasoline, often played at Al’s Bar. Instant electricity. Impromptu drive-thru wedding.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Reception venue?

Kim: Spaceland. I’ve known the owner, Mitchell, and all the bartenders for years. We had the place from two ‘til eight.

Craig: It was like watching a train full of people zoom by. Zillion miles per hour. Tippling. Celebrating. We had a western swing revival band—The Lucky Stars. Tex Williams’ style.

Spaceland transformed into Weddingland.

The week before Kim and Craig’s fifth wedding anniversary, they attend a Circle Jerks reunion concert at Spaceland as VIPs. Play catch-up with their crowd. Afterwards, Greg Hetson (now of Bad Religion) gives them a lift home.

Garden Party

“I’m a loser baby. So why don’t you kill me?”—Beck

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: I read an article about Gus Hudson in the music issue of Glue, and a little piece of my heart breaks. I have no clue who he is, but I find it distressing that former protégé Beck has blown this unassuming Flipside Records producer off: “It’s hard for us in the punk rock crowd to deal with bands that make it big. . . . We want the same relationship that we had before. And somehow that ends.”

The next day, I go to a party at Kim and Craig’s. Gus Hudson is there, wearing the same red shirt as his photo in the article. As if he just stepped off the page into the backyard barbeque. I have officially entered Kim’s own twilight zone.

Greek Theater

“We would talk every day for hours/We belong to the deadbeat club.”—B52’s

It’s a hot August night at the Greek Theater. On the bill are the Go-Go’s, b52’s, and The Psychedelic Furs. The Go-Go’s Behind the Music is in VH1 rotation. Talk of who’s who and old school. Kim and Craig meet and greet acquaintances. Artists and critics. We chat about Allison Anders and Kurt Voss’ Sugar Town.

Kim: I’ll see anything with John Doe in it.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: And that’s how I learned about John Doe, Exene, and the scene.

Almost Famous

“Every picture tells a story,”—Faces

Kim and Craig see Almost Famous. Coming out of the theater, a kid points to Craig’s bleached blond hair and shouts, “Eminem.”

Kim: Kate Hudson’s dad played at my sixth-grade graduation. The Hudson Brothers headlined Busch Gardens in The Valley.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Do you think Cameron Crowe’s film glams the rock ‘n’ roll film genre?

Kim: Definitely. The “Band-Aids” were too clean. Penny Lane had too many cute outfits. But what went on backstage—the bus ramming the fence, band on the run—that kind of thing did happen. Happened all the time.

Behind the Music

“The whole thing was about being yourself.”—Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten, The Filth and the Fury

Everything old is new again. Kim styles longtime client Billy Idol’s hair for his VH1 Behind the Music episode. Her eighteen-year-old assistant, Abrea, is in awe.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Well, you are a part of L.A. punk rock history.

Kim: Yes, that’s probably true.

Client Jean Sievers treats Kim to her client, Brian Wilson’s, Greek Theatre performance of Pet Sounds. Cocktails on the Redwood Deck, Kim reconnects with Billy prior to his Surfin’ USA and Fun, Fun, Fun encore with the legendary Beach Boy.

Kim’s clients are not always punk, but they do rock. She creates hairstyles for band members Beautiful Creatures before they rejoin the Ozzfest tour. Rock and Roll never forgets.

Silver Lake

“Stake her claim in Silverlake . . . chalking it all up to fate.”—Michael Penn

From atop costume stylist Houston Sam’s deck on Micheltorena—the same street that boasts silent screen star Antonion Moreno’s restored mansion The Paramour—Kim co-hosts a wedding shindig for close friends. It looks like the opening scene of Austin Powers. Eclectic collection of guests. Hair by Kim. Kim’s raucous laughter belies a cool reserve. A contradiction in terms, much like the music that changed her days to nights so many odd years ago. She holds her son, Aristotle. His mini tee forewarns: “Future Punk Rocker.” Shifting the baby from one hip to another, Kim casts a glance over the celluloid skyline. Balancing the dynamics of static and change in her ruby red go-go boots.

Postscript: After Kim, Craig, and Aristotle and their guardian angel, Felix, resided in one of Walt Disney’s former homes in Los Feliz, they purchased their current home in Eagle Rock, the day the city appeared on the cover of the Los Angeles Times as the latest in L.A. trendy real estate.

It’s a small world after all.

Mrs. Cooper (aka Shelly Johnson): “Scarlett” doesn’t suit you dear.

Becky (aka Lili Reinhardt): Well, I like it. It makes me feel powerful.–Riverdale

Jessica: What color lipstick are you wearing?

Helen: Well it’s three different kinds. I blend. I start with MAC Viva Glam 3.

Jessica: Uh-huh.

Helen: Which is a great base, and then I add Prescriptives Poodle on top.

Jessica: Oh my God I love Prescriptives, it’s the best.

Helen: I know, isn’t it?

Jessica: The moisture and the . . . It’s great.

Helen: Then I finish with Philosophy Super Natural Nude, which is more of a . . .

Jessica: Of a glossy, kinda?

Helen: Exactly, a little bit of shine.—Kissing Jessica Stein

Lili Kathleen Hardy is cute and a beaut who walks with aplomb and spunk to spare. What’s not to love about this Miss Ooh La, Montana girl, who once marched midway into a Taco Tuesday party with a loaf of ready-made garlic bread under her arm.

“This is just for me,” as she deftly heats the oven to 350 degrees.

Lil Lil’s tagline: “Garlic, I’m interested.”

Write Between the Lines is interested in Lil Lil’s beauty routine.

Through the looking glass, she graciously takes time to teach good face. Apply the maquillage to the visage.

Lili: So, what I do first thing, if I know I’m going to put my makeup on within the next hour, is moisturize. Prep my face so it’s hydrated and sticky. I won’t moisturize after I wash my face, if I have more time.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: What’s the rationale?

Lili: Moisturizing serum. I always start with my eyebrows, always.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Side note: We both go to Chandler Husband at the Beauty Strip for waxing.

Lili: Omg, luv Chandler. Shape the brows with concealer. Eyebrow pencil and a pomade. If I don’t really care, I’ll just use a pencil. I’ll always start back to front: fill in the eyebrow up to the front fourth. Blend it out with the spoolly brush using super simple hair strokes. Blend it out again so it’s not so harsh. More natural, not so blocky.

Then, I will set them with clear brow gel I like twice instead of once, so I know they’ll stay if I go out all day. Next, I’ll shape the brow with Anastasia “soft glam” palette, Jouer Cosmetics Essential High Coverage Liquid Concealer, so I know the shape they’ll take. I always start on the top part of below my brow. After the bottom I’ll do the top, same thing: create shape that stands out in sharp relief to the skin. If I make it too thin on accident, or I don’t shape it well enough, I’ll go back in with a brush.

Lili checks her look in the mirror and kicks up her heel.

Lili: Next eyes. I like to prime with concealer, then blend it out.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Why not foundation first?

Lili: Tons of fallout and it messes up your face.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: How do you choose your color?

Lili: I just look at the palette. I set my eyelids with translucent powder so it doesn’t crease. Tap, not swipe. Hmmm. Transition shade. Matte or shimmery?

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Matte.

Lili: Burnt orange.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Is that the same palette I use?

Lili: It’s Anastasia’s Soft Glam Eyeshadow Palette. You have Modern Renaissance. I do beat it into a pulp, using this Morphe M167. Blend with a big fluffy brush. Build up the transition color. Darker, Darker, Darker. Don’t go too fast. The transition color can be lighter or darker; neutral blends everything together. Deepen the crease brush fluffy more tapered Lexi 249.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: When did you start playing with makeup?

Lili: Twelve? I started doing it in 7th grade. I got serious when I was fifteen. I didn’t get good at it until I was sixteen, seventeen. That’s when I could actually pull off full glam looks and not feel stupid.

Lili’s hip shifts to one side, her feet Battement tendu into second position.

Lili: Once I’m done with the eyelids: eyeliner.

Lili locates the Kat Von D Tattoo Liner.

Lili: Yep, it’s a banger. My holy grail.

Wing flipping back and forth swoop with precision light brush strokes. Stops to admire the thick wing line that frames the matte shadow.

Peaches and cream complexion. Button nose, nary a blink.

Lili: Then I’ll check if the length to see if one is thicker or longer than the other. If so, I’ll make adjustments. False eyelashes: Black lash glue if I have liner, clear glue if I don’t. Glue on first until it’s tacky then I’ll put on mascara. I won’t curl them at all.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Which mascara do you use?

Lili: It literally changes every day. I pick at random. Loreal Telescopic Volumizer is a really good drugstore mascara dup for Too Faced Better Than Sex Mascara.

“I do my hair toss, check my nails

Baby, how you feelin’? (Feelin’ good as hell.)” Lizzo

Prep and prime.

Lili: Eye cream if I just washed my face. Put on the moisturizer with little dabs. While this setting in the skin, I get out my beloved beauty blender. I change it every three months. Always get your bb damp so it expands. I wring it out with a towel, and let it sit while I prime my face using a lil Bye Bye Pores primer t-zone. Also, sometimes if you take too much pore filler, it balls up in your hand that’s how you know.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Where do you buy your products?

Lili: Sephora and Ulta.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Nigel’s gives us the NoHo neighborhood discount.

Lili: Foundation literally depends on what is the right shade of face. At home I use a tray. While traveling, I put it on my hand, then dot it all over my face. Polka dots. I like to use a brush to blend it. It’s just not attractive to see a line between foundation and the real face. Concealer under eyes, dab with beauty blender.

Big fluffy brush with translucent powder.

Contour.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Blush changes every day.

She plumps up a half smile for the apple of the cheek, and brushes the blush swiftly away towards the hairline.

Lili: Melt everything into your face so it’s not so cakey. Fan everything with the highlight’s brush. Put some on my nose and cupid’s bow. If it’s too intense, blend it out a little.

Highlight brow bone matte on my eyes’ inner corner is my fave thing to do. Eyeliner outer corner of my lash line blend out with brush. Urban Decay setting spray 30 sprays drench my face doesn’t move for the rest of the day.

Touch ups. Brush teeth. Do lips. Outline with Kylie Cosmetic Candy K. It is my basically my lip color, but better. Fenty lip gloss, and that’s it.

Write Between the Lines takeaway? Blend always. Lili blending in? Hard(l)y.

by LB Nye

Claudia said she couldn’t take me, but here she was moving other people around so she could take me right away. A manicure emergency.

An emergency ‘cause the funeral is in a couple of hours and I’m not gonna bury my mother with chipped nails. Gel polish ‘cause death gets the good nails.

Claudia tore in with the cuticle clippers and the files. Nobody ever said Claudia was gentle. Nails come out good, though. She says, “Don’t flinch, I got sharp implements here.” I say, “You’re gonna draw blood.”

Acetone smells like my first manicure, hanging with Mom and my aunts. Makes you feel like a grown up, walking around with those perfect nails. Base coat and top coat. Perfect, Claudia got the skills. Then the color. Red, red, red, the color of Chianti. And rub ‘em down. Mom likes the pale colors, pinks and such. But she doesn’t have an opinion, anymore.

So, the thing you do is, after Claudia is all done, is you set your fingers under UV light, a minute, maybe two. Two if you want it to really last. There’s some chemistry in there, free radicals set off by the UV wavelengths, bonding up, hard as crystal. So, I sit still; the radicals get to be free.

I tip Claudia good and she taps the back of my hand, “hang in there.”

Nicest she’s ever been to me.

by KEM Huntley

Within walking distance, is the North Hollywood Amelia Earhart Regional Library. Scanning its NoHo calendar, I am lured in by a recent literary event vignette:

“King Tut, the invention of the automobile, a TV game show, and a tiny cactus parasite all profoundly affected the face we show the world. How did red lipstick impact the women suffrage movement? With seemingly unrelated trivia, DeBus reveals odd connections and presents some of her vintage makeup collection.”

I am most intrigued to visit the one-story Spanish Colonial Revival style stucco Mission style library that honors our most famous aviatrix. Its humble beginnings—two bookcases housed in a corner of the City of Lankershim’s post office.

With a stylish air and natural flair for storytelling, San Fernando Historical Society Board Member Maya DeBus presented, “History & Make-up: ‘How Events Shaped How We Look: Intriguing, Whimsical, and Little-Known Connections.’”

Ms. DeBus opened with the acknowledgment that embellished faces are global, attributed to religion, magic, power, and sometimes—witchcraft. She showed the Norman Rockwell “Girl at Mirror,” to point out how we gaze at our blank slates, dreaming of a transformed state. (Fun Fact, my second . . . maybe third . . . cousins modeled for at least two of The Saturday Evening Post covers. One as twins. Great Uncle Edwin Eberman co-founded The Famous Artists School with this Americana Life’s gent.)

Ms. DeBus subscribes to the notion that “Red Lips Kiss My Blues Away”— a sentiment to which I concur. “Cosmetic” comes from the Greek word, kosmētikḗ, “the art of dress and ornament. The art is ancient, and Ms. DeBus fascinated the crowd as she regaled tales of Queens Elizabeth and Victoria, actresses and ladies of the evening, painted ladies, and “Blue Bloods”—society ladies faces paled with products such as Dr. Campbell’s “Arsenic Complexion Wafers,” who drew blue lines on the sides of their faces to indicate veins.

Ms. Debus ordered the art of the artifice both chronologically and by facial features. Inside this California native’s bag of tricks and historical tidbits (also known as the “ring purse”), included intel on Max Factor, who was originally a wigmaker in Imperial Russia. After emigrating to first NY then LA, he discovered the need for film stars to wear something other than theatrical make-up, aka “grease paint” under the blaze of hot camera lights. The make-up spells he created so well oftentimes “disappeared” on set, compelling Max to set up shop in Hollywood.

Further factoids include New York City’s Suffragette’s paraded wearing red lipstick supplied by ardent feminist Elizabeth Arden. Plus, the cochineal insect, essentially produces carmine that deters predation, and used for red lipstick—oftentimes used for the same purpose.

Ms. DeBus has not yet published her findings; however, she is looking forward to receiving kTVision’s 4th Grade teacher’s field trip report: MayaSpeaks@aol.com. Perhaps I can tease her purple prose into a polished, published piece of true art. Or, I can just steer her towards Bésame Cosmetics in Burbank. Founded out of a fascination with art, history, and beauty by artist, cosmetic historian, and designer Gabriela Hernandez; her chic boutique boasts a “. . . vintage makeup brand which honors the style, spirit, and sensibility of female beauty.” Not to mention, she wrote the book, Classic Beauty: The History of Makeup.

I wear House of Bésame’s 1941 inspired gilded, lipstick bullet, “Victory Red.” My glam gram, Bow Bow, once the object of Oscar Hammerstein the II’s affection, would be pleased prettily.

Postscript” “Collage is not all that she does,” was the first snippet of conversation I overheard in room of perhaps twelve library patrons. Completely random and in no way in regard to Ms. DeBus; however, an epitaph I may use for a future grave marker.

by Julio Peralta-Paulino

Day was well past coffee and breakfast — even if at Parthenon the first meal of the day wasn’t much more than some dusty Danish — when Heisenberg’s green line rang.

“Oh, yes the teen vampire project. I like this draft. What are we calling it?”

He asked without any expectation of a response.

“The sophomore version. Yes yes the problem as I see it is that it should either be a vampire film or a werewolf movie, but this mixture it’s simply too either or and I don’t want that and I don’t think that what’s her name wants that.”

There was a pause as if to give the novelist some credit for coming up with the series of words that had made a book and was now being transcribed into a screenplay by a scribbler that knew, in the opinion of Heisenberg and for that matter Parthenon, what it truly meant to write.

That is to say, being oblivious to nearly everything but the all important plot and the not so important sub-plot.

“I’d love to get that Soy Popula on this, but that brat thinks she’s Hollywood royalty. Next thing you know, we’ll be stuck making the next Norman space sci-fi adventure vehicle set in Paris. I got enough worries . . . Let me make some calls and see what the schedules are like for Winter season. I’ll get back to you, in the meanwhile, cut out the dogs, you know the wolves, and make it something more sexy — uhm, maybe he turns into bird — a pretty bird — half vulture and half falcon. Now, get right on that before I sign the director.”

Heidelberg hadn’t seen it all, but he’d seen enough. He especially held witness to the continual lack of major worldwide box office at Parthenon. It was fair to say he was an agitated man in need of something spectacular for his prodco. Parthenon was one of the old time players. Old as far as anything could possibly be old in an ever-young city like Los Angeles. It was rather simply mostly farmland when cinema was taking its early steps. A dream much like Las Vegas, but a drama that would quickly evolve into one of the world’s most alluring attractions. When America went to war, Parthenon went to war—with R rated films. Even so, none of their movies were ever among the top-grossing of all time, they didn’t have the type of weekend openings one might be inclined to associate with a name such as Parthenon Studios.

Every so often H, as Heidelberg was nicknamed by those near enough his acquaintenances not to be threatened with being fired or worse, would say to himself, “Well, Gigantic was massive and they had to split the loot with Teamworks, and after I’ve been here we had Reformers but also in partnership with Twenty Cent Locks; it’s probably one of those movie things.” Sometimes, when H practiced infidelity and he did so every Thursday and every long weekend available to himself and his revolving convoy of escorts, he’d whisper afterwards: “The thing I worry about is the Artisan Curse.” Of course, he wouldn’t explain what that was to his momentary mistress except to add: “They had a good thing with the Rare Witch Project, but they went for the sequel and it killed them.” If the fun was outside the ordinary, H would include a concluding thought to his confessional whisper: “It’s the age of the sequel, but some movies simply cannot be made.”

Months passed, H was never pleased with the photo-play in progress, much as loved the potential. “It needs something. It has romance, sure. I don’t know, maybe a bimbo mobile?” From his experience, it was clear, when a movie starts to feel like work then it might not be worth producing. It might just start to feel like a workload to the goer that has to carry it for two hours in a dark room.

The afternoon came early. One conference call and suddenly his secretary handed him the green line and the words went around the room, “Let the lawyers find a new team for this screenplay. I already got one with the same title out, it’s been knocking at my distraction for months, and we really need to concentrate on that love story with the three-legged cat.”

When the first Vampire film did well, there was some uneasiness surrounding Parthenon and H. Still, it was — as many people tend to say — “one of those things.” They got lucky or they deserved something for having the balls to put Christmas Nicci as a piglet in a stinker. A tolerable folly. Once in a while, to his wife, in the late evenings, he’d say, “Maybe I should have had some more patience with the werewolf side of the thing.”

Powerful men are not usually prone to remorse or regret. Tears are rare, although fears might be fruitful. H was being driven to one of the hideaways just outside L.A. in the Autumn when the sequel to the project he had sent back into negotiations appeared.

The long lines made him think, “Hmmm kids, looks like another winner, this business is insane. No telling what might strike up the ticket band.” He took a Tambien, which was a popular medication in those days even if the side effects included self-extermination. He went to bed, shaking from the text-message realization that it had made seventy million in a few hours showing. The words echoed like cold leftovers in the gut of his thoughts, “This isn’t even the big weekend.”

That first not even the big weekend the movie grossed 153 milliion domestic. It was bigger than many of the big movies and cost a fraction of what they had been budgeted. It was big news. Excellent news, in fact, for the industry. It simply wasn’t news that Parthenon, and especially H could relish.

After only two weeks the world-wide total was estimated at four hundred and seventy million dollars. All of it within an international recession, possible flu-epidemic, and the talk of global warming looming over the earthly population.

One might have expected a place like Parthenon to demote or even deliver Heidelberg his walking papers. “Didn’t the guy from the mailroom look a lot like H? If you can’t get me on screen anymore then I don’t have half an hour to make your pasta al dente.”

Of course, often something as dramatic as the sequel’s triumph turns heads so entirely that nothing is said and things go on as they had before the rights were let go to some other contender.

Day was well past teas and biscuits—even if at Parthenon the first meal of the day wasn’t much more than some hasty fruit—when Heisenberg’s private line rang.

“Oh yes. That reminds me, I need something stronger than my current prescription. Would Morphine be too difficult?” He asked, entirely expecting the Rx Fedexed before the pome disappeared from its decomposing position alongside the oversized Rolodex.