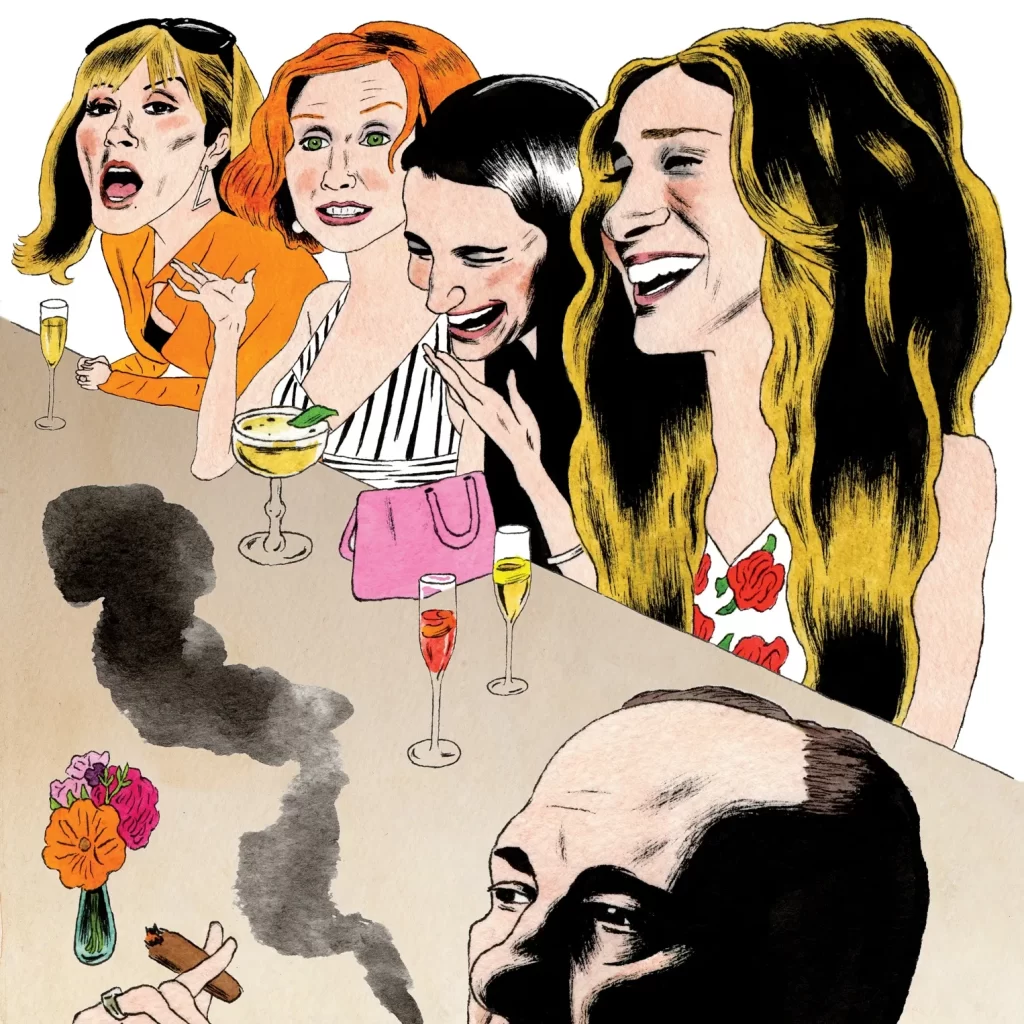

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

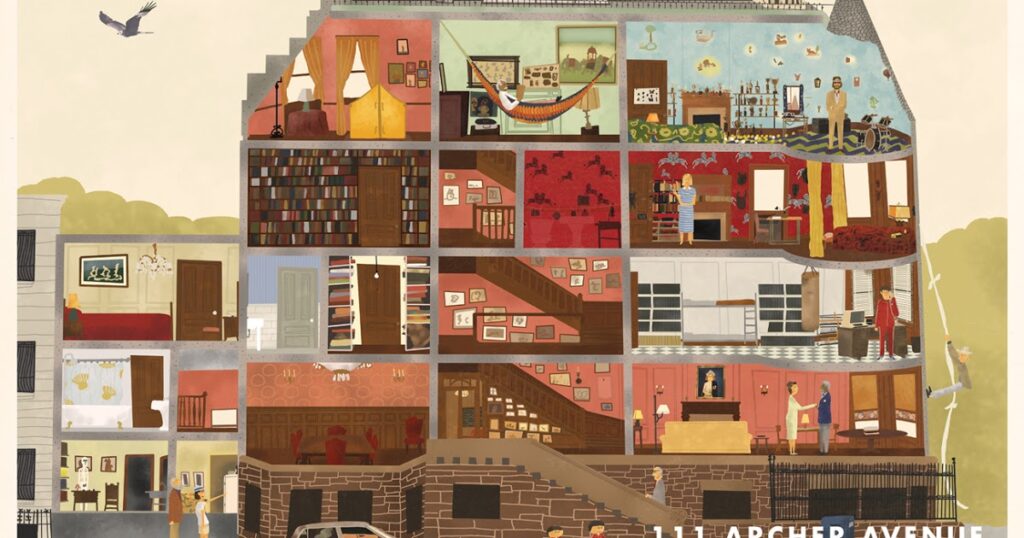

Illustration by Andy Friedman

Charlotte: I’ve been dating since I was fifteen. I’m exhausted. Where is he?

Miranda: Who? The White Knight?

Samantha: That only happens in fairy tales. (1)

“Modern women need cheat sheets to remind us romance isn’t dead.” (2)

Jane Austen’s heroines do not only exist in early nineteenth century literature. “Cher” is an up-to-date Emma in Amy Heckerling’s Clueless. The titular character in Bridget Jones’s Diary is reminiscent of Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennett—only now she’s a hip London “singleton” navigating among the “smug marrieds.” Written in the spirit of Ms. Austen, four New York singletons offer their own Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing with cosmopolitan wit in HBO’s Sex and the City.

Faithful to the ideal of romantic love is sweet Charlotte, originally an art dealer and now a divorcee. Miranda, a corporate lawyer, represents sensibility bordering on skepticism. Damn the torpedoes sexual temptation is embodied in publicist Samantha. Main character Carrie Bradshaw considers and synthesizes these and her own disparate perspectives on the love and war front. Carrie shares Elizabeth Bennett’s “quickness of observation.” (3)

She poses questions, carries out research, and reports on the city that never sleeps’ escapades and exploits. (Note: The first episode of the series begins with Carrie interviewing an English journalist named Elizabeth, and ends with her bumping into her own Mr. Darcy, enigmatically christened “Mr. Big.”)

These single successful career women are engaged in love/lust relationships confined to twenty-two square miles of Manhattan. Like the village in which Jane Austen locates her select society, Sex and the City, based on author Candace Bushnell’s column, is only a “. . . small subset of high-profile New Yorkers: fashion people, media honchos, money people, famous-for-fifteen-minute-artists.” (4)

Sex and the City’s universe is specific—yet its themes are universal. What intrigues Sex’s writers, and ultimately its audience, are the same kinds of thematic conflicts Austen writes about:

“[Jane Austen] is interested in dramatizing sex in everyday social life—in the drawing room rather than the bedroom. The courtship plots she creates allow her to explore the relations between sex and moral judgment, sex and friendship, sex and knowledge—that is, between sex and character. . . . The very publicity of sex in Austen’s novels—the constant awareness, the relentless dramatization—is what makes her examination of social life so powerful.” (5)

The writers for Sex and the City are not restricted to the drawing room. What happens behind closed doors is on screen in full view, yet the salacious is only a diversionary hook. Discourse on mores and manners, particularly givens associated with gender roles, is what constitutes the show’s substance, much like in Austen’s world:

“The lives of Jane Austen heroines, who spend much of their time at balls, dinners and on extended visits, should not . . . be considered trivial. Essentially they are engaged in receiving an education in manners, the subtleties of which can be fully explored only in the context of the formal social occasion, and are thus being prepared for their role as arbiters of manners and preservers of morals. By undergoing this process, and by eradicating the deficiencies in manners . . . the heroines eventually become as useful to society as any politician, soldier or clergyman.” (6)

Sex and the City is a comedy, and as such the leading ladies have a vast comic repertoire to draw from (broad humor for Carrie’s “fashion roadkill” (7) pratfall; black humor for Miranda’s mother’s death) (8). Comedy is the essential accessory for trifling issues: Manolo Blahniks or Jimmy Choos shoes? as well as the severe “running with scissors” (9) situations. The 5th’s season finale leaves the New Yorkers still girlfriends, still single, and still cynical—yet romantic enough to fall sway to the strains of a song playing at an acquaintance’s wedding reception: “Is that all there is? Is that all there is? If that’s all there is my friends, then let’s keep dancing . . .” (10)

As ever, everything that’s classic is fabulous again. Whether we are perusing Jane Austen’s literature or tuned into Sex and the City, we can all relate to the “delightful commentary upon the little foibles of human nature” (11)—a “perpetual human comedy, in which we all have to play our parts.” (12)

Postscript:

Twenty one years after first publishing the Jane Austen Heroines’ article, And Just Like That showcases the character, Amelia Carsey, as a voiceover artist performing a dramatic reading of Pride and Prejudice.”

Footnotes

1 “Where There’s Smoke.” Writ. Michael Patrick King. Sex and the City. Created by Darren Star. Dir. King. HBO. Season 3: Episode 31. June 4, 2000.

2 “Are We Sluts?” Writ. Cindy Chupack. Sex and the City. Created by Star. Dir. Nicole Holofcener. HBO. Season 3: Episode 36. July 16, 2000.

3 Swisher, Clarice. Ed. Readings on Jane Austen. San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1997.

4 Franklin, Nancy. “Sex and the Single Girl.” The New Yorker, July 1998: 74-77.

5 Fergus, Jan. “Sex and Social Life in Jane Austen Novels,” in Jane Austen in a Social Context. Ed. David Monaghan. Macmillian Ltd., 1981.

6 Monaghan, David. “Jane Austen and the Position of Women,” in Jane Austen in a Social Context. Ed. David Monaghan. Macmillian Ltd., 1981.

7 “The Real Me.” Writ. King. Sex and the City. Created by Star. Dir. King. HBO. Season 4: Episode 50. June 3, 2001.

8 “My Motherboard, My Self.” Writ. Julie Rottenberg and Elisa Zuritsky. Sex and the City. Created by Star. Dir. Michael Engler. HBO. Season 4: Episode 56. July 15, 2001.

9 “Running With Scissors.” Writ. King. Sex and the City. Created by Star. Dir. Dennis Erdman. HBO. Season 3: Episode 41. August 20, 2000.

10 “I Love a Charade.” Writ. Chupak and King. Sex and the City. Created by Star. Dir. Engler. HBO. Season 5: Episode 74. September 8, 2002.

11 Moore, Catherine. “Pride and Prejudice.” Masterplots. Ed. F. N. Magill. Englewood: Salem, 1976.

12 Priestly, J.B., “Afterword,” in Four English Novels. Eds. J.B. Priestly and O.B. Davis. New York: Harcourt, 1960.