Boogie Nights

by KEM Huntley

This ’70s joyride through LaLa Land’s exotic erotic film scene is a fresh twist on the extended family and the curious ties that bind. Writer/Director Paul Thomas Anderson presents a story that coolly dismisses accepted societal standards. He populates his screenplay with empty souls who follow their own (a)moral code, yet instead of alienating the audience, he convinces it to care.

A key component of this success is its underlying story structure. An exact storyform, however, is not immediately evidenced. At times it feels like an overall story with a goal of obtaining—the characters all want something: sex, drugs, fame and fortune. Other times the goal appears to be being—the characters believe their lifestyle is temporary and want to take on another role. Buck dreams of being his own boss—ruling the “Super Cool Stereo World.” Following the grand argument may be somewhat difficult when the plot progression falters, for example, after Dirk Diggler (main character) and Jack Horner’s (influence character) falling out, the relationship story steps aside for a considerable amount of screen time in favor of the other three throughlines. Still and all, dressed in its best polyester double knit, Boogie Nights turns story into film art as the acting, cinematography, soundtrack, and so forth spins you through its disco party.

What follows is one “rolleroid” snapshot perspective of this Goodfellasesque epic:

Pornographic film director Jack Horner opens the door to his private paradise as the setting for the overall story. “It resembles the Jungle Room at Graceland” and comes complete with Jacuzzi, swimming pool, and its own (basement) film studio. Talent resides at this secure (thematic issue) funhouse where reality is distorted by white lines and Cuervo Gold. It is here where the changing industry (story goal of progress) is debated:

FLOYD

The video revolution is upon us—and our role is critical.

COLONEL

Jack, please understand that this is not an argument . . . this is a fact (overall story catalyst).

JACK

What?

COLONEL

I think that there is a serious case to be made for the price and the gamble on the whole idea of a home video market . . . two, three years from now, everyone’s gonna be able to walk into their local supermarket and buy or rent a videocassette . . . film is just too damn expensive . . . the theaters are already planning converting to video projectors.

Jack represents a different way of thinking. He has the ability (thematic issue) to direct “stellar, sexual standouts” but his true desire (thematic counterpoint) lies in making porno films with “stories.” Jack discovers (story driver–action) the next big thing, Dirk’s big thang, and the relationship story throughline sets in motion as each takes a fixed position on what it means to be a director and an actor. The thematic issue of confidence illustrates the positive aspects of their relationship. Jack is certain of Dirk’s value (relationship story catalyst), and this assuredness plays out–making the director amenable to the kid’s ideas—his own stage name and his own action series (Brock Landers: Angels Live in my Town).

Sweet-natured and trusting (main character symptom), Dirk is a physics character, whose first approach to a problem is to work it out externally (doer). His male mental sex has led him to an environment where he can be “a big, bright, shining star.” An inexperienced (thematic counterpoint) actor, Dirk’s raw skills (thematic issue) are applauded in the adult film world (“Diggler delivers a performance (doing) worth a thousand hard-ons”).

The relationship story concern is explored in the preconscious, where Dirk’s anywhere, anytime, sexual impulses (“I can do it again if you need a close-up”) are filmed under the direction of Jack. The fantasy world Jack fabricates for Dirk eventually inhibits their relationship. Dirk boasts he blocks his own sex shots “. . . and he (Jack) gives me flexibility to work with the character . . .” His vanity pricked, Jack laughs it off.

Jack’s tolerance (problem of accurate) of Dirk’s escalating ego and cocaine habit reaches its limit, illustrated when Dirk, strung out, screams, “YOU’RE NOT THE BOSS OF ME!” (solution of non-accurate) and Jack immediately fires him (overall story consequence of preconscious).

Anderson deftly indicates how the effects of the objective characters’ individual circumstances create dilemmas for them: the effect Amber Waves’ career choice has on her custody battle (no visiting rights), the effect Little Bill’s wife’s flagrant sexual escapades have on her husband (murder in cold blood), and particularly, the devastating effect Dirk has on Scotty (heart wrenching humiliation).

For Dirk, doing the hustle no longer means choreographed booty shakes—it’s risky street business with ill effects (main character problem). Trapped in a nightmarish parody of his own action films (Guns! Firecrackers! Sister Christian!) Dirk finally realizes he has no other option but to stop his wayward Wonderland course—that only he can be the agent (cause) of his change—a solution shared in the overall story.

Stripped of his pride, a wiser (unique ability) Dirk stumbles back to his Hollywood home. By this time, Jack has resolved his own problem of sticking to the proven method of producing porno on film to successfully using videotape (unproven). Preparing for his next feature with Jack, Dirk’s angst has evaporated (story judgment good). He is cool. He is sexy. He chants to his mirror image—“I’m a star, I’m a star, I’m a star, I’m a star, I’m a star, I’m a big bright shining star”—and karate kicks to the credits.

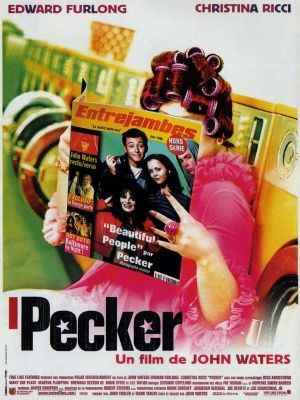

Pecker

by KE Monahan Huntley

Pecker is a Dramatica grand argument story emanating from John Waters’ weird, yet very real, world. Pecker (main character) is a “snappy go happy—happy go lucky” amateur photographer. His sidekick, and occasional assistant, Matt, is a pro at “five-finger discounts.”

PECKER

Dude, you’re gonna get popped.

MATT

Not me bro—I’m invisible.

Pecker’s girlfriend, Shelley the “stain goddess” (influence character), operates the local laundromat—The Spin n’ Grin.

PECKER

You’re my Venus De Milo.

SHELLEY

You’re crazy. You see art when there’s nothing there.

Pecker’s parents run business ventures that run in the red. His mother’s thrift store outfits the homeless; his father’s dive bar cannot compete with the strip club (overall story focus-temptation) across the way. Little sister Little Chrissy is a sugar maven; big haired big sister Tina bartends at the downtown gay discotheque. Grandmother Memama has a roadside pit beef (!) sandwich stand, and believes her Blessed Mary statue speaks (overall story solution-faith).

Pecker is open (main character unique ability) to the variety of life in and outside of Hampden, a district of Baltimore: “If it wasn’t for you, Peckerman, I’d never know this shit existed.”

To Pecker, “everything always look good” through the lens of his camera.

Pecker has taken pictures all over Baltimore for his first exhibit to be held at the fast-food joint where he works, The Sub Pit.

The fliers he has plastered around town (main character approach-doer) catch the eye of Rorey. She approaches (overall story catalyst) Pecker, checkbook in hand: “Your pictures are amazing. They’re the real thing. . . . I’d love to give you a show in my New York Gallery—if you’d be willing.”

At the opening, Pecker and his “culturally challenged family” are introduced to the New York art world that anoint him: “A brand new art star.” Pecker snaps pics of the chic crowd because: “Life is nothing if you’re not obsessed.”

The family returns to Hampden to find their home burglarized. Rorey encourages him to: “Take pictures, Pecker. This could be your next show. Your dad’s loss. Your mom’s sadness. Get close-ups.” As quickly as the community has embraced Pecker’s fame, they are ready to disown it—and him. The police officer investigating the case admonishes the boy: “What they call art up in New York young man, looks like just plain misery to me.” Shelley entreats him not to: “. . . become (consequence) an asshole, Pecker. I beg of you, do not become an asshole.”

All manners of catastrophes hit. Little Chrissy is put on Ritalin. Matt is caught shoplifting. Tina’s fired. Memama is accused of faking Mary’s miracle. Pecker can no longer take original photos: “I’m trying to get new stuff, but everyone knows me now.” As one potential snapshot subject snaps: “Some people don’t feel like being art.”

When Rorey puts the moves on Pecker (main character focus-temptation), an act witnessed by Shelley—it is the last straw for the photographer (main character response-conscience). Assuring Shelley he loves her “more than Kodak” (relationship story thematic counterpoint-commitment) he turns his back on New York and says: “They can come to me this time . . . I’m going to have my own show right here in Baltimore (mental sex-female).”

Shelley learns (overall story requirement) to appreciate the colors of her world (influence character resolve-change), and the town realizes its favorite son is true blue (main character resolve-steadfast). New York travels to Baltimore by limousine, and Pecker’s “outsider art” is a brilliant success (overall story outcome). All applause for Pecker and “the end of irony.” A newscaster inquires, “So what’s next, Pecker?” To which he replies, “Well. I’m thinking of directing a movie.” (main character concern-future)